The development of technology is accelerating exponentially. Moore’s Law states that the processing power of computers doubles every two years, with the corresponding cost of such a computer halving at the same rate (1). This has led to new developments in almost every aspect of life, be that in the medical, financial, or automotive sectors. These new technologies, when first introduced, are expensive and inefficient, however, in accordance with Moore’s Law, over time this technology improves, becomes cheaper and therefore commercially viable.

This is the case, for example, with 3D printers. My first 3D printer was given to me by my grandma as a Christmas present when I was 13. I viewed it as a project machine, one which I upgraded, tinkered with, and tested the limits of. And at one point I had six printers, busily whirring away in my room [Figure 1]. Experimenting with such a new technology forced me to learn, from first principles, the basics of electronics and manufacturing. I get immense satisfaction from designing and printing my own objects or parts, it is seemingly intrinsic in me. But it was only 15 years ago that such a manufacturing technique was only available in industry (2). Now, anyone can order such a machine for a fraction of the original price and have a device that can produce almost any object.

Figure 1 – An array of 3D printers in my house (not all of them)

Virtual reality and the ominous-sounding “Metaverse” – an entirely digital space where users can own (virtual) land, invest in cryptocurrency, or interact with one another – is another example of this. Events such as lockdowns have forced people to communicate solely online. The rise of such a space – a by-product of the pandemic – has thrusted revolutionary VR technology to the forefront of society. Many companies are engaging with the platform; a 2020 report from consultancy PwC predicts that nearly 23.5 million jobs worldwide will use AR and VR by 2030 for tasks including employee training, meetings, and customer service (3). From my own personal experience, I have seen first-hand the profound effect of VR, an incredibly novel concept, on users who have never experienced it [Figure 2]. Watching teachers, students and friends step into the virtual environment for the first time is not only a magical moment for me but a hugely humbling and wondrous moment for the user. They oftentimes react with incredulity, in shock that they now exist in a completely alternate world. The usual five fundamental senses don’t apply, there is no smell, nor taste, your only means of touch is through controllers, and what you are seeing is not really there. Such a headset forces you to be acutely aware of your emotions and innate reactions. VR is so novel, that users often feel ill after fundamental tasks such as walking or picking up virtual objects – the body is seeing something different to what you are feeling, thus tricking you into believing that you are hallucinating. This “hallucination” is a natural reaction to poison, so the body triggers its defence mechanism: vomiting, the only means by which the “poison” can be ejected. The technology is not at the level of full immersion – allowing full interchangeability between the physical and digital worlds – but is nonetheless imminent.

Figure 2 – Mr Burton helping me plan engine suspension using VR

The concept of “flight of fancy” – an idea or narrative that is extremely imaginative and presents itself to be completely unrealistic – can be linked with technological progression. The same instant emotion that we as humans feel when interacting with VR is seen throughout the digital landscape. Tesla’s market value was more than the ten highest ranked global car companies combined, despite manufacturing much fewer cars (4). This is mostly down to the “hype” around the company. Musk has announced multiple vehicles in the past years, none of which have yet been available, whilst making other dramatic claims on car-autonomy that are yet to be proven (5) (6). It is these car concepts and promise-of-the-future that spur huge investment in the company; he is not offering anything tangible or real in the present. It is this intangibility that fascinates me: how humans can be influenced by concepts or ideas and have strong, fundamental, impulsive reactions to them.

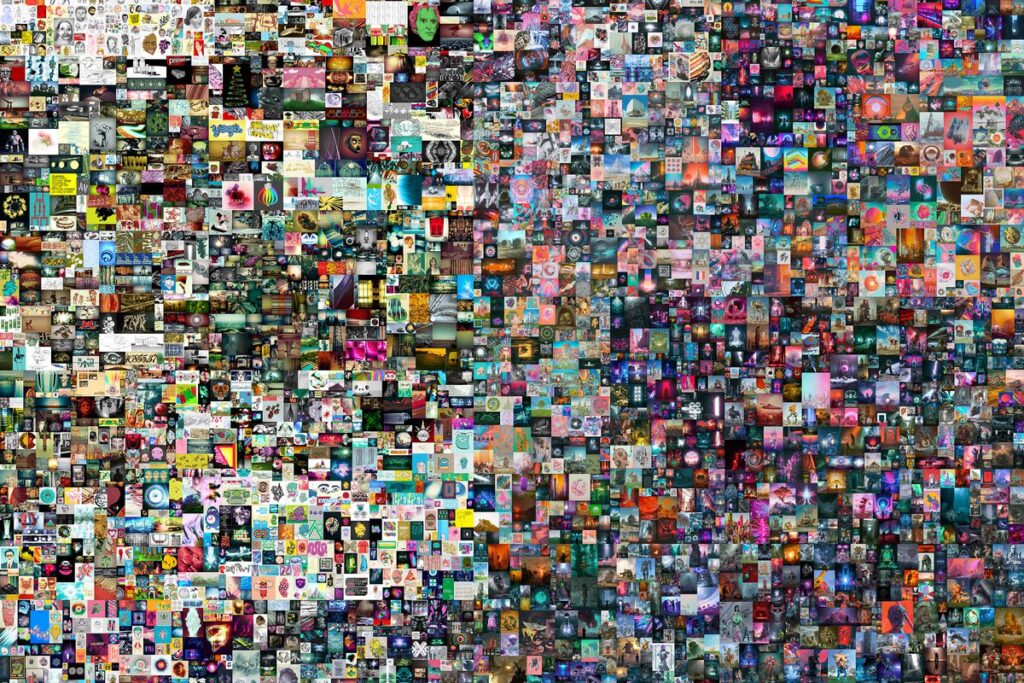

NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) are also such an example. NFTs are essentially a means of selling digital art online. The buyer doesn’t “own” the artwork in the physical sense – anyone can make copies of or have replicas of the artwork – it merely proves that they are the legal “intellectual property owners”. As in anyone can have an image of the Mona Lisa in their house, but no one (other than the French state) actually owns it. Such a medium for transaction has given rise to reactionary artworks. For example, a video, sold as an NFT, of a man burning a Banksy art piece has sold for over three quarter of a million pounds (7). Or a Croatian tennis player who sold part of her arm for £5,000 to raise sponsorship money – e.g. the buyer can choose a tattoo to put on that part of the arm (8). This new form of selling art plays on the theme of “hype”. Many of the most lucrative artworks – digitised monkeys, caricatures of famous political figures – are so popular because of either the seemingly arbitrary value that the art market places on them, or because purchasing the NFT itself gives the owner access to, for example, an exclusive yacht club or a play-to-win game [Figure 3]. Digital art is becoming more and more popular given how accessible the market now is. According to a report published by Nonfungible.com, backed by L’Atelier, NFTs made up 16% ($17 billion) of the Global Art Market in 2021 (9). Where previously one would have to place bids in an auction house, now art pieces can be bought for millions of pounds with the click of a button

Figure 3 – most expensive NFT sold at $69m: Everydays: The First 5,000 Days, Beeple

Thomas Heatherwick’s approach to architectural design is unique to his studio; “I have a strong sense that every project is an invention, which is not a word I hear being used in architecture courses”. I find this thinking to be really intriguing. His studio wishes to break the status quo of the architectural norm and has no “signature style” nor does it follow a “fixed design dogma” (10). He views each project individually, seeking to maximise its “social impact” and invent a space that functions fundamentally on the human level (10). Another fascinating aspect of his studio is the entirely collaborative setup, something I have frequently enjoyed doing myself throughout my own project. He doesn’t employ just traditional “architects” or “engineers” but “landscapers” and “problem solvers”, each of whom question and contribute to their respective parts of the design (10). This logic has enabled the studio to produce buildings that are not only aesthetically beautiful but sit perfectly in the surrounding environment and encourage human interaction. I have experienced personally, how ultimately boring and uninspiring engineering can be when stripped of creativity, individuality and partnership. Given my passion for designing and making things, so much so that I wish to pursue engineering to a degree level, I wanted to apply Heatherwick’s approach to problem solving to my own project. Instead of following a set textbook or PowerPoint with no room for creative manoeuvre, I wanted to use engineering principles and software imaginatively, guided by ideas and themes; as Heatherwick comments; “An interest in ideas is a sign of human life. People are fascinated by what the future is going to be – and the future is going to be an accumulation of ideas.” (11) This links back to the core theme of the project. Ideas, concepts, emotion is what peaks the innate human reaction; ancient, dogmatic instructions serve to only replicate what has already been done.

Upon a visit to London, I visited several of Heatherwick’s projects, to understand from a first-hand perspective how the spaces function. The first was the Paternoster vents in the City of London [Figure 4]. Rather than a building, these served as a cooling inlet for an underground electricity substation. Given the proximity to St Paul’s Cathedral and the office buildings around them, the structure doesn’t intrude on the surroundings, and hides its function beautifully. The forms follow a geometrical pattern, emulating that of origami.

Figure 4 – Visiting the Paternoster Vents, London

After this I walked over the river to see the repurposed entrance to Guy’s Hospital. The studio redesigned the rear entrance to the building, specifically recladding the adjacent boiler house, that looked ugly and would often overheat. When I visited, the flowing ripple-like metal weave skin acted as a visual signpost to help visitors locate the entrance [Figure 5]. The texture is designed such that it discourages graffiti, and the surrounding area is very calm with minimal traffic (the studio also improved the surrounding roads and pavements). Overall, this created a calm and visually fascinating entrance to an otherwise dated institutional building.

Figure 5 – Up-close to the Heatherwick cladding by Guy’s Hospital, London

What I enjoyed most about the Heatherwick structures was their effectiveness in emotionally engaging the viewers/users. This was most apparent when I visited Coal Drops Yard, behind King’s Cross Station [Figure 6]. Not only is the shopping and café complex visually stunning, respecting the Victorian history of the buildings, but the structures themselves seemed to encourage a warm, community feel in the area.

Figure 6 – Visiting Coal Drops Yard, London

Away from the bustling transport hub, it felt a comforting place to be: many families around me were enjoying barbeques on the surrounding grass, whilst students and friends sat together, talking, and playing with one another [Figure 7]. The building itself has lots of seating around the middle floor, further promoting socialisation, whilst the adjoining roofs allow for a viewing area of the skyline beneath it. As mentioned before, the studio’s spaces work on a human level, encouraging social interaction, whilst respecting the buildings’ history and surrounding environment. Heatherwick’s approach of focusing on the user is key to the studio’s success.

Figure 7 – Surrounding social area

A body of work that I found to be of very personal interest is Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Matter [Figure 8].My project begins with the disassembling of a defunct lawnmower engine. This component may seem like exactly that, a mass-produced part that only serves the purpose of moving an object in a certain direction. However, this was of deep sentimental value. It was part of a lawnmower that my dad had been using for as long as I could remember. He would store it in his shed, folded up, leaning against the wall, and use it to cut the grass on a weekend. The nostalgic value of this engine and what it was once part of is immeasurable. This links to Parker’s installation. She viewed the humble shed in a similar light: “[It is a space] Where you store things you cannot quite throw away. Like the attic, it’s a place where toys, tools, outgrown clothes and records tend to congregate.” (12)

The process of then exploding the shed symbolised exposing and removing the archetypal Sunday Morning along with the sentimentality and nostalgia associated with that. Perhaps indicating a transition to a different weekend routine, moving on from the old to progress into the future – much like the aforementioned progression of technology.

But perhaps most interesting, was the reconstruction of the shards that remained from the violent explosion. The fragments after the detonation would have settled randomly on the ground, resembling a crime scene: Parker described them, when laid out on her studio’s floor, as a “morgue” (12). The deathly shards were as lifeless as blades of grass when cut by a lawnmower. Reassembling the parts, to form an “exploded view” was deeply exciting for me, given the precision and accuracy required to create such a projection – something only seen in the engineering sector. The exactitude in re-piecing former events resembles the process used by forensic architects to chronologically decipher, for example, the bombing of a building. Again, it is as if Parker has exploded the shed and reassembled it to create a new space, an evolution from the old one. This new space is highlighted using a central light in the middle of the piece, casting complex, random shadows on the surrounding walls, adding a new dimension to the room. A dimension that is not tangible but can only be interacted with through sight and enabled through artificial means (electricity) – exactly like a VR world.

Figure 8 – Cold Dark Matter, Cornelia Parker

Conrad Shawcross’s series of sculptures entitled Paradigms also powerfully accentuates the repetitive, habitual process required to make patterns and the science and creative engineering behind his sculptures link back to the breaking of traditional engineering dogma [Figure 9]. Throughout the series he uses a tetrahedral shape as a basis, both because of its mathematical properties but also because it was the shape that scientists 150 years ago thought the atom resembled (13). This has since been proven wrong, something fascinating to consider: science is sometimes incorrect. “It’s [misidentification of atom structure] an example of science being over-eager and taking a philosophical idea of something unobtainable and using it in the real world.” (13) Perhaps the New Age digital revolution will not do as well as first hoped? Perhaps integrating computers into a human world will end in catastrophe? Will investors eventually see through the hype and recognise the lack of substance? A 2021 research paper based on the use of AI in autonomous cars in urban settings, found that even AI has unknown biases that can sometimes jeopardise passengers’ safety (14). Researchers had to counter this with an “unlearning algorithm” that would reverse this bias. Shawcross’s sculptures are algorithmic yet seem like they are on the point of collapse. However, the engineering behind the structures ensures this doesn’t happen. I too used a tetrahedral shape to produce digital crystals, using a repetitive method that would spawn complex, organic shapes. The repeated process that is central to this body of work resembles the repeated process in mowing the lawn. So much so that it becomes muscle memory, a routine my dad followed every few weekends, as if such a mundane act were a continuous timestamp throughout his life. The Paradigm sculptures, given the scientific planning behind each of them, also remind me of the “exploded view”, as seen in Cold Dark Matter. Whereas Parker’s piece was random, a by-product of an intensely violent event, Shawcross’s pieces are accurate and seem to obey the laws of physics. Due to their geometric intricacy, they also cast patterns of shadows onto the walls, that are regimented and crisp, in stark contrast to Parker’s sporadic shadow forms.

Figure 9 – Paradigms, Conrad Shawcross

Roger Hiorns’ processes and themes running through his Untitled body of work was another source of inspiration and thinking that I employed in Sentimentality of Concept. He transformed an obsolete BMW engine by allowing inorganic copper sulphate crystals to grow in and around it [Figure 10]. I am intrigued by his process whereby Hiorns simply allows the crystals to grow without interference. But even the growth of crystals was stunted as to allow them to develop forever would require infinite resources – an impossibility. This parallels with the idea that a blade of grass has its growth periodically stunted due to the lawnmower. The concept of allowing a process to occur naturally but within boundaries is another core theme to my project, be that trying to develop complex UV textures for my digital crystals, only to be hampered by my computer’s processing power, or the restriction in sales of cars/electronic goods due to a limit of microchips. My own lawnmower engine had its life curtailed, instead of choosing to fix the engine, my dad simply bought a new one. The sheer aesthetics and beauty of the installation are what captivated me the most. It reminds me of coral and sea life gradually, over decades, reclaiming sunken vessels in the sea. It poses, again, the question that the engine has run its course and that it is time to transition to the next phase of drivetrain technology. This is shown when I modify the lawnmower engine to crush various “useless” objects, highlighting what a once functioning component has been reduced to.

Figure 10 – Untitled, Roger Hiorns

This concept of reduction is seen in Hiorn’s, again untitled, atomised jet engine installation [Figure 11]. This was completed by a complex scientific process whereby the engine is melted, and chemicals are added to transform it into dust. Exactly like the copper sulphate engine, this piece indicates the end of the use of the jet engine, highlighting its futility. The process of atomising such an intricately engineered component proves how quickly all the effort that went into making it safe, reliable, powerful etc can be undone. And the idea of doing such a thing to an engine is unfathomable to me, the concept alone was enough to hook me.

Figure 11 – Untitled, Roger Hiorns

The integral component to my project is the user. The emotion from the interaction with the technology lies with the person using it. After all, what is all this immersive tech for if there is no one there to view it. As pioneering doctor Brennan Spiegel once said about VR, “Virtual reality is like dreaming with your eyes open”. Technology such as this has been used to help patients combat pain, further learning in classrooms and treat mental illness; the underlying theme being the often life-changing effects on humans. Moore’s Law is currently not being obeyed by most technologies – the rate is in fact increasing at an accelerating rate beyond that of this law. AI, VR and blockchain technology is here to stay and all people of all ages will be directly interacting with it in the imminent future.

Bibliography

1. Gianfagna, Mike. What is Moore’s Law? Synopsys. [Online] Synopsys, 6 30, 2021. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://www.synopsys.com/glossary/what-is-moores-law.html#:~:text=Moore’s%20law%20is%20a%20term,doubles%20about%20every%20two%20years..

2. Turney, Drew. History of 3D Printing: It’s Older Than You Think. [Online] Redshift by Autodesk, 8 31, 2021. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://redshift.autodesk.com/history-of-3d-printing/.

3. Higginbottom, Justin. Virtual reality is booming in the workplace amid the pandemic. Here’s why. [Online] CNBC, 7 4, 2020. [Cited: 03 21, 2022.] https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/04/virtual-reality-usage-booms-in-the-workplace-amid-the-pandemic.html.

4. Richter, Wolf. Tesla’s Market Cap (Gigantic) v. Next 10 Automakers v. Tesla’s Global Market Share (Minuscule). [Online] WOLF STREET, 10 26, 2021. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://wolfstreet.com/2021/10/26/teslas-market-cap-gigantic-v-next-10-automakers-v-teslas-global-market-share-minuscule/.

5. Aitken, Peter. 5 times Tesla couldn’t keep a promise about its electric vehicles. [Online] INSIDER, 7 25, 2019. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://www.businessinsider.com/tesla-elon-musk-electric-vehicle-broken-promises-2019-7?r=US&IR=T.

6. Andrew Hawkins. [Online] The Verge, 5 7, 2021. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://www.theverge.com/2021/5/7/22424592/tesla-elon-musk-autopilot-dmv-fsd-exaggeration#:~:text=Tesla%20is%20unlikely%20to%20achieve,Tesla%20representatives%20told%20the%20DMV..

7. Criddle, Cristina. Banksy art burned, destroyed and sold as token in ‘money-making stunt’. [Online] BBC, 3 9, 2021. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-56335948.

8. Caron, Emily. CROATIAN TENNIS PLAYER SELLS AD SPACE FOR AN ARM AND A NFT. [Online] Sportico, 3 31, 2021. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://www.sportico.com/business/commerce/2021/croatian-tennis-player-sells-arm-nft-experiment-1234626090/.

9. Gaskin, Sam. Out of Nowhere, NFTs Now Constitute 16% of the Global Art Market. [Online] OCULA, 3 11, 2022. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://ocula.com/magazine/art-news/nfts-now-constitute-16-percent-of-the-art-market/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=The%204th%20Indigenous%20Art%20Triennial%20%20Crossovers%20at%20Torontos%20Power%20Plant%20%20Art%20Dubai%20Highlights&utm_content=The%204t.

10. Studio – About. [Online] Heatherwick Studio. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] http://www.heatherwick.com/studio/about/.

11. Thomas Heatherwick Quotes. [Online] BrainyQuote. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/thomas_heatherwick_554034.

12. The Story of Cold Dark Matter. [Online] Tate. [Cited: 3 21, 2022.] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/parker-cold-dark-matter-an-exploded-view-t06949/story-cold-dark-matter.

13. Shawcross, Conrad. Psychogeometries. s.l. : Laurence King Publishing, 2019, p. 56.

14. Stelling, Jack and Atapour-Abarghouei, Amir. “Just Drive”: Colour Bias Mitigation for Semantic Segmentation in the Context of Urban Driving. s.l. : Cornell University, 2021.